Saturday's earthquake near the coast of Chile, which registered a magnitude of 8.8, was actually significantly stronger than the January 12 earthquake which devastated Haiti with a magnitude of 7.0. While damage, casualties and civil unrest are at catastrophic levels in Chile now, the degree to which the destruction affected Haiti more could be measured on the same kind of exponential scale used to measure the magnitude of the earthquakes themselves. It's worth asking why lesser tremors caused so much more damage. Two immediate answers present themselves: poverty and preparedness.

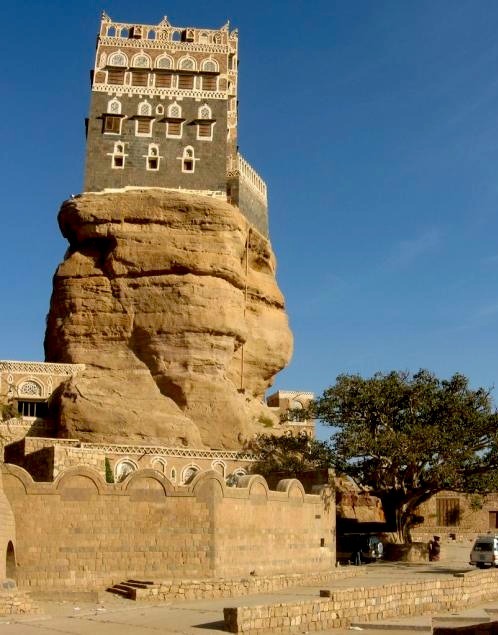

Chile's location on the Pacific Rim puts it in a very high risk area for seismic activity like earthquakes. In fact, the strongest earthquake on record, with a magnitude of 9.5, had its epicenter in

Valdivia, Chile on May 22, 1960. Additionally, nine out of the ten largest earthquakes on record are along the Pacific Rim (Saturday's quake will take the #5 slot on this list). Because of this historical precedent for large scale seismic events in this region, engineers have focused on planning for events such as these in the way that cities are laid out and in the way buildings are constructed. The Caribbean is not the same hotbed of seismic activity, though there are

several significant Caribbean earthquakes noted over the last 500 years, and so earthquake safety isn't as high on the list of building specifications as it is on the Pacific Rim.

Even if it was, however, Haiti's history of poverty and political unrest make it difficult to put together and put in action any kind of coherent plan for this. Haiti has a GDP per person (a commonly used measure of a country's financial health) of $1,300, compared with $14,300 in Chile and $46,900 in the US, making it one of the poorest countries in the world (compare it even with the GDP per person of the Dominican Republic (which shares the island of Hispaniola with Haiti, and which was relatively unaffected by the January quake) of $8,300). While Chile

has had its own share of political unrest, violent turnover has been a recurring feature in

Haiti's history, compounding the economic hardship with a lack of consistent government support. When the majority of the population lives in unofficial, improvised shanty towns, even the strictest building code isn't going to protect that largest part of the people. When essential needs like food, water and medical attention are hard to come by even when things are running normally, any upset will make them near impossible.

Right now, the death toll from Saturday's earthquake in Chile stands at 723, and is not expected to rise much higher, though the region is still feeling aftershocks of 5+ magnitude. The record-setting 1960 quake claimed about 1,600 lives. Those numbers are tragic, regardless of larger context. However, it's still boggling to think that January's quake in Haiti, which released about

1/500 of the energy of Chile's quake, claimed more than 200,000 lives. Chile's death toll would have to nearly triple to represent 1% of that in Haiti. This mismatch between destructive power and destructive effect further highlights the tragedy of the situation in Haiti, because it suggests that it was the pre-existing desperation of the country's situation more than the event itself that caused the most damage and that the same event elsewhere might have done relatively little damage. In the wake of it all, it provides us with an opportunity to think of the broader reaching effects of poverty around the world, and how many of these places are a quick shake away from being Haiti all over again.